Imagine a situation. You’re in the classroom, and the aim of the lesson or stage is focused on speaking skills. You tell students what you want them to talk about, and then…nothing really happens. Not much speaking is generated and what should have been a nice 15 minutes of animated discussion, quickly fades into two or three short exchanges. Most teachers have experienced something like this. So – how can we make our speaking lessons and tasks more productive? Perhaps the first question we should ask ourselves, is why the students didn’t speak.

Think about some possible reasons for lack of speech and then see if your ideas are similar to mine.

- Maybe the students don’t have knowledge of the subject matter.

- Perhaps they don’t say much because they don’t have the appropriate lexis or grammatical structures to complete the task.

- It’s possible students don’t have any ideas immediately ready to express.

- Maybe the task doesn’t have any purpose, or students can’t see the point.

- They could be uninterested in the topic.

- Topics can be culturally unsuitable, too personal or taboo.

- The students could be shy and feel self-conscious in speaking.

- They could be more comfortable with activities where there is a correct / incorrect answer, and not with giving their opinions.

- They may not be working with a partner / partners that they get on with, or feel comfortable with, or perhaps the fact that their partner is a lot stronger than them is intimidating.

So, those are some possible problems. Now let’s look at what we can do to minimise them. Let’s look at two examples, both of which probably wouldn’t sustain a quality, longer speaking task, for several of the reasons mentioned above. How could we do things differently? Think about how you might change and manage each of the two tasks to make them work better, then read on to compare your ideas with those below.

Example 1

Students discuss in pairs – ‘What do you spend your money on?’

Possible difficulties

On the positive side, this question is personalised, meaning students will not need any special knowledge. However, they may still need more direction and some time to think, otherwise the task may not last very long – students will run out of things to say. There could also be more of a purpose to the task – is there motivation for students to speak? We also need to be careful that we don’t ask students to give information that they may feel uncomfortable about. If one student doesn’t have a lot of money compared to others, they may not want to talk about amounts.

The improved version

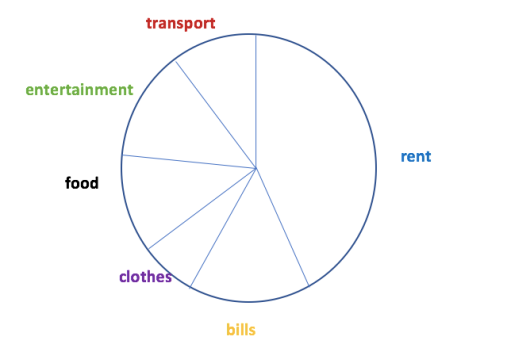

The teacher gives instructions ‘Look at this pie chart. It shows what I spend my money on and how much I spend in one area compared to another. What can you tell me?

The teacher then elicits ideas, answers questions and provides students with more information about each category – in other words, they briefly model the task so students know what is expected of them and have some help with ideas. This can be important – if we don’t give students an example, and show how much we want them to say, they may simply give one or two sentences and consider themselves finished.

For example, the teacher says;

Listen to me talking about what I spend my money on. Is it similar to you or different? Does anything surprise you? Take notes.

‘ I spend most of my money on basic living costs. For example, I spend almost 40 percent of my money on rent.That’s quite a lot, but it’s the most important expense because I need to live near good public transport… etc.

Once students have listened to the model, taken notes and compared them with a partner, the teacher can now tell them to draw a similar pie chart. Additionally, if this is going to be a longer speaking task, the teacher could choose to focus on / input some useful language that featured in the model (for example, a third of, almost half off, most of etc. ), to ensure students have the language to complete the task better.

Students have time to think, draw and make notes. Once they have done this, they can describe their chart to their partner / group and see who is the most similar / most different to them in their spending habits. They could repeat this multiple times with different partners if the teacher wishes to extend the activity. Alternatively, while one student describes their pie chart, the other can listen and try to draw it.

Why is this better?

The activity now:

- Gives students time to think and plan so they definitely have something to say

- Provides an example so they know the kind of information they should include and the level of detail they should go into

- There is communicative purpose to the task – students must find out who is the most similar / different to them

- Maintains personalisation but doesn’t force students to give information they are not comfortable with

Example 2

Students tell each other in groups ‘about a time when you were the victim of a crime’.

Possible difficulties

As with the previous activity there is the possibility that students may have been a victim of a crime and find this unpleasant to talk about, or, they may never have been a victim of a crime and so have nothing to say. Additionally, they may not have appropriate vocabulary to complete the task, or may need time to remember appropriate words, phrases and ideas.

The improved version

The teacher shows students a picture/s about a crime (real – from a newspaper, or teacher-made, but nothing too sensitive / violent). ‘This picture is about a crime that happened (insert time and place). With your partner, try to guess what the headline in the newspaper was.’

Students discuss, and when they are finished the teacher shows then the real headline for comparison.

Here the teacher may need to input some vocabulary – for example witness, statement. etc. This will depend on what your students already know.

The teacher then sets out a situation. ‘The police are asking for witnesses to the crime. Some of you are going to be a police officer and you will take the statement of the witness. Some of you are going to be witnesses and you will give your statement to the police and answer any questions.’

Students are then divided up into two groups; one of police officers and one of witnesses. The police discuss the details of the crime and what questions they want to ask. The witnesses discuss what happened. When they are ready, a police officer and a witness are put together to complete the role-play. Afterwards the police could comment on whether they think the witness was reliable or not, and why.

Why is this better?

The activity now:

- Avoids any need for students to discuss something unpleasant that happened to them.

- Ensures they have enough to say through the use of the headline, picture/s and the preparation time with a partner of the same role.

- Increases students’ confidence because they have time to share ideas before performing the actual role-play.

- Encourages more self-conscious students. Role-plays often get students speaking more because they don’t feel as ‘seen’. They are ‘acting a role’ rather than being themselves, which often creates more of a sense of freedom. It’s a bit like giving the student a mask to wear.

- Ends in a task which mimics real life and so should give some purpose.

Summary – Top Tips

- Get students interested in the topic at the beginning of the lesson. This could be through visuals, setting a task with a short related video, pair or group discussion, brainstorming, reading a short text etc.

- Choose topics and tasks that have relevance to their lives and that they have some knowledge of.

- Think about giving students a model / example of the kind of thing you want them to do (this can either be through you or a recording).

- Consider inputting some language that will help the students be better able to complete the task. To find out what this language might be, do the task yourself and see what chunks of language you needed to use.

- Give students time to prepare – e.g. thinking time and making notes.

- Try to give the speaking task purpose – make sure students have something to achieve. Rather than just ‘talk about…’ we need to make it clear why they are talking. For example, to find three things you have in common with your partner, to make a decision together, to persuade a partner/s, to solve a problem etc. This is likely to increase motivation.

- Try playing background music while students are speaking. This helps shy students feel less exposed.

- Often getting students to stand up and / or move around seems to make them speak louder and more. Perhaps this feels more natural or they feel freer when moving around, or perhaps not – but it often helps!

- Vary the groups and experiment with putting shy students together or with a stronger partner and seeing which they respond better to.

- Avoid over-correcting and create a classroom atmosphere where students feel safe to take risks with language.

Two very beneficial approaches to conduct speaking actuvities.

Empathy is a good route to come up with probable solutions.

LikeLike